Chevron

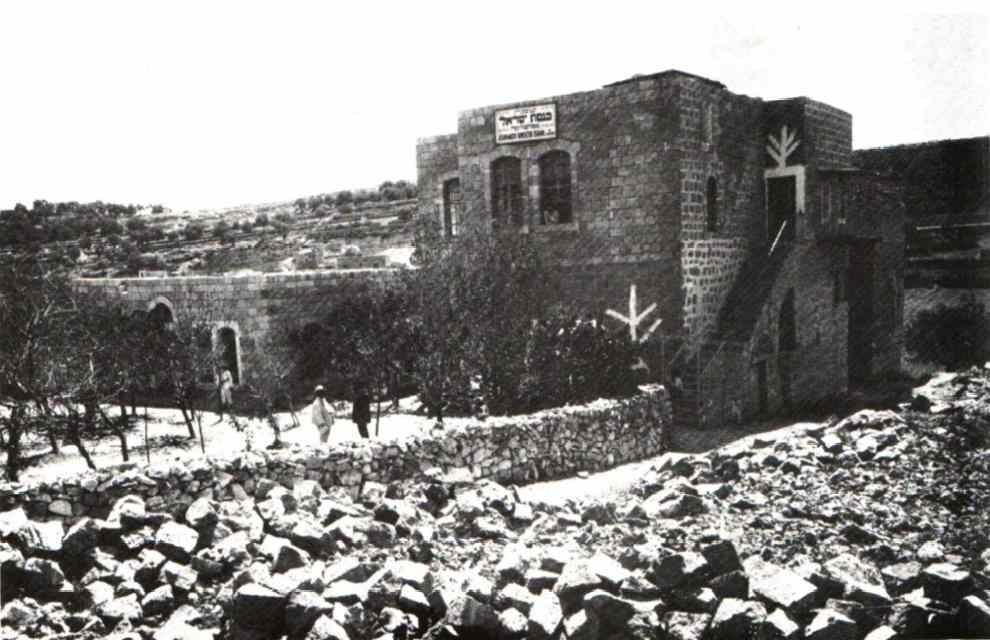

Yeshivas Kenesses Yisrael (Slabodka), Chevron 1911

This Shabbos, 18 Av, marks the 80th yahrzeit of those killed in the 1929 massacre in Chevron.

The message of Slabodka, the yeshiva that relocated there before the massacre, is realizing the potential and dignity of every person you encounter. Dan Slonim Hy”d not of the yeshiva, although he was always there when they needed assistance. As he was for every one, both the Jews, the local Arabs, even the very members of the mob who slaughtered him, his wife Hannah, his little son Aharon, and 19 others in his home.

The message of Slabodka is also the dignity of oneself, knowing one’s true worth, and how to strive for the kind of greatness Hashem Yisbarakh created you capable of acheiving. Whether it was the constant learning of Simchah Yitzchak Broide, who was killed in the yeshiva, his blood spilled across the gemara; or the chessed of Alter “Ashpooler” Sher, one of the students who founded a gemach within the yeshiva; R’ Moishe “Warsawer” Grodzinsky, a talmid of the Chafeitz Chaim who was known to greet every person first, and with a smile — whether the yeshiva student in his bording house, the sheikh or the Arab waterboy. (Reb Moishe Warsawer was killed just weeks before his son’s wedding.)

These are just a few portraits of those who were killed that day. All of them very distinct, made in different molds. And yet each led a life of reaching for greatness.

The Alter of Slabodka with Students, Chevron

The following was written by Rabbi Leo Gottesman of the West Side Congregation and a Yeshivas Chevron Alumnus, on the occasion of the first yahrzeit in 1930. He spoke of those who came to Chevron, and told stories of those he knew who were murdered there. I used that section as one of the sources for the quick sketches I wrote above. However, I chose to include Rabbi Gottesman’s closing words of hope in full — that G-d is still with us, and it is for us to continue the ideals for which they lived.

WHAT shall we derive from all this?

Shall we allow the hopes and dreams and prayers of over eighteen centuries to be washed out by the blood of the martyrs of last August? Shall we throw up our hands in discouragement and call ourselves defeated.

No! That is unthinkable!

Reading over what I have written before; reading the account of the wonderful, the pure, the noble souls whose earthly careers were snuffed out in the twinkling of a gory, degraded passion for which the Arabs will never be able to forgive themselves when they have grown more enlightened, it might seem indeed that we are in a helpless situation. It might seem that in addition to our own helplessness we are faced with an absence of divine sanction; that God, Who permitted that unspeakable atrocity, has not cared to look with favor upon our efforts to reestablish ourselves spiritually and materially in the land of our forefathers. But to think so woud be to fall into an enormous error.

It would be wrong to hold in mind only the few score martyrs who fell beneath the weapons of the mad mob—who fell thus and thereby rose so high that it is given to few to hold rank with them in their greatness. It would be wrong not to give thought to those who were saved. And by this I mean not the vast multitude, the whole Jewish population of Palestine, more than 150,000 souls, whose survival may be ascribed to the purely natural cause that the danger did not come very close to them. I mean rather the hundreds who, though engulfed by the flames, were nevertheless drawn out of the fire; and were saved by such means that it is hard not to say— miracle, hard not to perceive the hand of Providence in it, hard not to realize that their being saved means that God has not averted His face from us but stands by yet to spare His children and speed us on the road to victory.

Yes, a few died; but many more were saved. Let us not make the mistake of looking only upon the little heap of sacred ashes. Let us gaze with understanding eyes upon the survivors, the living evidence of our ultimate victory. Because I have said so much in detail about those that died, let me say something about those that were saved; and I will leave it to many others to build up the remainder of the encouraging picture. I will content myself by concluding this brief record with a few accounts of how some of our fellows escaped the fate that threatened alt.

I have already written of some that survived, the manner of it being nothing short of miraculous. There were Lezer Yanishker and the young sister of Hannah Slonim, who were hidden in a closet. Whence came so much strength to the arm of a single youth, holding a door shut against the efforts of a mob——?

And there was the wife of Zaimon Welan-sky who, clinging to her husband, fell beside him in a swoon as he was stabbed by many knives, and was covered with his blood—so that the Arabs though they had stabbed her too. By this her life was saved. How much less than a miracle is it?

And there was William Berman’s younger brother. Who can say by what miracle he was permitted to live even where his brother and his friends were murdered. What stopped the Arabs, who thought him dead, from making sure of it?

Not all the Arabs in Hebron participated in the massacre. Some remained aloof, and some helped the intended victims to escape. Many hid in pits, in trees, in bushes—anywhere to be out of sight when the torrent broke loose. And many were concealed by friendly Arabs. One Arab gave shelter to thirty people, including the old Rabbi Slonim.

Two young boys were caught alone in a house when a mob began to break in the door. They ran up to the roof. The mob entered and plundered what they could. Then they began to look for persons—and were soon bound for the roof. The trembling boys sought a way of escape. They looked down into the yard, and there was an Arab—beckoning to them to jump down. They declined at first, being afraid of him. But seeing the mob about to come up, they were forced to take the leap—the height not being great. The Arab below took them by the hand and led them to a safe place and guarded over them until the worst was over.

Among those whose escape borders very close upon the miraculous is Rabbi Mosheh Mordecai Epstein, the venerable Dean of the Yeshivah. He was in his own house when the attack began, and there were twenty-five people with him. The doors were fastened. They were not molested at first. But late in the day, when the Arabs were finished with their horrible work elsewhere, they turned to the Rabbi’s house.

As they were actually breaking in the door, some trucks transporting soldiers from Beer Sheba to Jerusalem passed through Hebron and though the street where the Rabbi’s beleaguered house stood. These soldiers had not been sent for by anyone in Hebron. They had no business there and had no knowledge that anything was wrong in the city of the patriarchs. They were merely passing through on their way to Jerusalem . But they arrived in the nick of time. Five minutes later would have been too late to save many lives.

The soldiers, not knowing what was going on, but seeing a violently behaving mob, fired a few shots in the air—and the cowardly pack dispersed. They were in no mood for anything but the murder of the defenseless men and women and children. Thus, at the last moment, at the very moment of resignation, the Dean, and over a score of people with him, were saved.

Too numerous are the escapes, natural and, in a sense, miraculous, for me to write of all that I have heard about, though many of them are so extraordinary that it is hard to resist putting them on record. But I will content myself with giving just one more here—that of my own brother—whose escape was hardly less noteworthy or miraculous than any.

My brother was studying in Hebron . Having received a check from home, he was in Jerusalem on Friday, August 23, purchasing a suit. Late in the afternoon he took the auto that runs between Jerusalem and Hehron, intending to return in time to be in Hebron for the Sabbath.

The locality was in a hum of excitement. Many rumors were afloat—among them a rumor that trouble was brewing for the Jews in Hebron . My brother’s friends tried to dissuade him from returning to Hebron . They begged him to stay over in Jerusalem for the Sabbath and if things remained quiet in Hebron he could return to the Yeshivah on Sunday. But my brother, like the other American boys, was not afraid. He was confident that no harm would befall them. He insisted on returning for Shabbos to Hebron and, against the wise counsel of his friends, took the auto for Hebron and was soon on his way.

It happened that he was the only Jew on the auto. All the other passengers were Arabs. As soon as they were on the road, he began to feel most uncomfortable. The Arabs were whispering among themselves, and casting peculiar glances at him, and pointing to him when they thought he was not looking, and smiling in an unpleasant way. He began to feel that his friends in Jerusalem had been right.

What if indeed some horror was afoot? The Jews in Hebron were not ignorant of the danger. There was nothing his presence could contribute if trouble really came. And were not these snickering Arabs pointing to him as “another customer” riding carelessly into the jaws of death? He began to wish he had not started out. He wished he could go back. If only there were some way of withdrawing from this unfriendly company! Might they not attack him on some lonely part of the road? But what excuse could he offer for having the car stopped? And if he began to run, woud they not chase after him?

Suddenly a great gust of wind arose and carried his hat off a good way back on the road. He began to shout to the driver to stop—he must recover his valuable hat. The driver was in no hurry to hear him. He took his time at it, and slowly, very slowly, brought the car to a stop. In the meantime the car had gone on a considerable distance and the hat was far, far back. My brother alighted and loudly requested the driver to wait there with the bus until he got his hat. Was there not a malignant grin upon the driver’s face as he promised that he would certainly wait for him?

My brother hastened along after his hat. What with the distance the car had gone, and the velocity of the wind, the hat had been left very far behind. When my brother got it, he was practically out of sight of the auto. Not stopping to dust it, he fixed the hat firmly upon his head and began to walk at a very rapid pace—back towards Jerusalem —and let the automobile wait there for him.

And so it happened that the next morning, Saturday, August 24, the day of the massacre at Hebron, my brother was not there, but safe in Jerusalem . Had it not been for that blessed gust of wind that carried his hat off, my brother would have been in Hebron together with Bennie Horowitz and William Berman, and the others—and who knows what might have been?

One of my friends, to whom I told of this miraculous escape, remarked that that was no ill wind which blew Friday afternoon on the road between Hebron and Jerusalem. Indeed it was not an ill wind but a wind of Providence, of that same Providence Who has watched over the Jewish people and preserved it throughout the long night of the exile, Who watches over it still in the dawn, and will continue to do so through the bright new day that is speedily coming.

תהא נשמתם צרורות בצרור החיים

May their Souls Be Bound in the Bond of Life

… and may we follow the path that it was not their lot to complete.

Recent Comments